The Lost Giants | Recipient of the 2026 grant

Founded in 2023, The Lost Giants (Amy Webb, Ruth Webb and Lisa Schneidau) are West Country designers and creators of giants, processions, and beasts of disguise. Through the forgotten British art of community-based giant making, they re-imagine folktales and magical characters to reflect the imagination embedded in local places around the UK. With the support of the Ffern Folk Foundation, The Lost Giants will work with an environmental community group to co-create a new processional giant shaped by local landscapes, ecologies and folklore.

In Discussion

Can you describe who you are, and tell us a little bit about The Lost Giants?

AMY: We are Amy Webb, Ruth Webb and Lisa Schneidau, and together we are The Lost Giants - a collective of artists from different creative backgrounds, brought together by a shared love of giants, beasts and the joy of procession.

Once upon a time, processional giants were a familiar sight in towns and villages across Britain - striding through streets in religious pageants, civic celebrations and seasonal festivities. Over time, many of them disappeared; packed away, pulled apart, banned, forgotten, or left to sleep in attics. The word “Lost” in our name, speaks not only to what has vanished, but to what can be rediscovered. Our work is about picking up those threads - reviving, reinventing and carrying the tradition forward.

What do you think is so appealing about giants in our contemporary context?

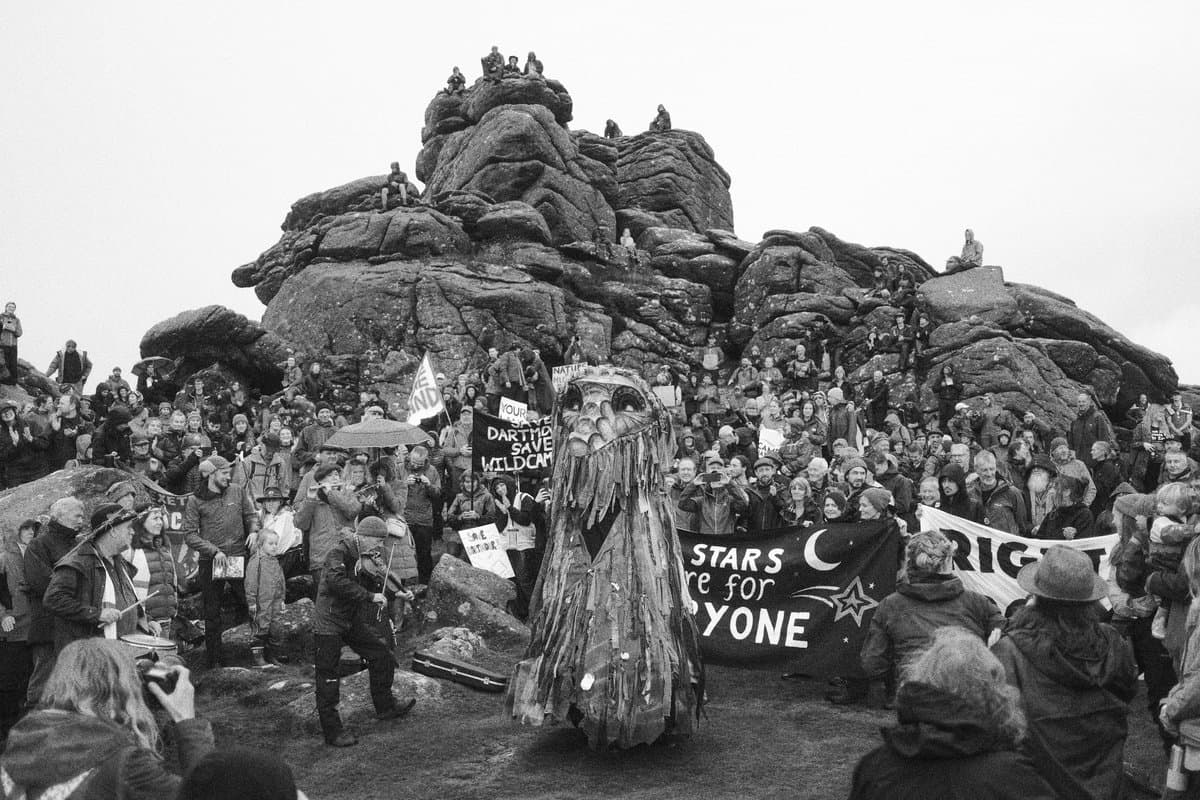

RUTH: For us, their true power lies in the fact that they visit us in our world, our streets, our common land, our town square. In this moment when they rise up and walk the land we know, we can experience the feeling that anything can happen, at any time, anywhere! We believe that is an important thing for us all to experience; it holds the potential to make us feel that anything is possible and that the world is alive with story, and meaning, which we can all be part of.

Because of the space they need, giants are also an opportunity - they need a community to exist. They ask for collective believing, for the sharing of resources and space. Unlike most other folk traditions, giants (quite rightfully) take up a lot of space and need a rather large bed in their fallow times. They offer us a reason to come together, to work with others in our local community and to find common reasons and purpose to take to the streets in celebration or defiance.

"Giants offer us a reason to come together, to work with others in our local community and to find common reasons and purpose to take to the streets in celebration or defiance."

It seems to me that in much of British folklore the figure of the giant is linked to the formation and shaping of the land. Why do you think giants are so persuasive in making us think about our relationship to the land?

LISA: In the old tales of Britain and Ireland, giants are a witness to (and sometimes a relic from) ancient times when the land and its perils were much closer and more difficult to ignore. Some stories describe how giants formed our landscape by hurling rocks around or creating great valleys, hills and scree. Others tell of giants as guardian spirits of the land.

Sometimes these are peaceable creatures, like the Cornish giant at Carn Galva forever rocking backwards and forwards on his loganstone, gazing out to sea. Other times, giants are formidable foes to be defeated by human heroes, usually called Jack (remember that one? Fi, fi, fo, fum…).

Giants are a clear reminder of our vulnerability in a modern, virtual world, and of the proper order of real things; they can give agency to those parts of the more-than-human world that we may not be listening to. In the new stories we create (and all stories start somewhere), giants can be Ted Hughes’ Iron Man and Woman, the monster under the bed, the power of a river fighting back or the anger of the changed sky itself.

"Giants are a clear reminder of our vulnerability in a modern, virtual world, and of the proper order of real things; they can give agency to those parts of the more-than-human world that we may not be listening to."

Through your work, you show a preoccupation with using natural and reusable materials to create your creatures. Can you dwell on how nature guides your process?

RUTH: For us, it's about foraging, learning, gathering and growing and also rummaging, car booting, charity shopping and freecycling. It’s about trying one's hardest to honourably represent both the vision, the to-be-created being, alongside honouring the land and not being so stubborn as to admit that sometimes what you do actually need is some gaffer tape!

A key ambition of your project is to co-create a new processional giant with a local community group. In an increasingly globalised society, why do you think that it is important for art making to reflect a sense of local place and community?

RUTH: Our need for kind, creative, meaningful, playful communities grows stronger the further apart and more isolated we feel. To be in action, to sit and talk and plan, to create with, to make noise about something important to us, to connect with others, to reach out past our normal social spheres, that is where we each have the chance to enact real change. Although we may not as individuals be able to affect the wider world, if each of us were engaged in such pursuits...well, we would!

I'm certainly not claiming that giants will save the world, but they do have the capacity to bring us together. As with many other collective art projects, a giant needs all of the talents, all the ages and all the people in a community to bring it into existence.

Your project has a strong strand of research running through it. What do you hope this will bring to the folk community?

AMY: Processional giants appear again and again in fragments throughout our history: in religious pageantry, civic celebrations, folk traditions and more recently, environmental action. But those stories and giants are scattered, and so far they haven’t been brought together in one place. We want to follow those threads, join the dots, and help build a shared understanding of giant-making and the part it plays in British folk culture.

We believe that traditions stay alive through openness and sharing. With Ffern’s support, we want to begin creating accessible ways for people to exchange knowledge, skills and stories. We hope to connect those already involved in giant-making with people who are just discovering it.

Finally, can you let us know some of your favourite giants (and giant making groups) from around the UK?

AMY: There are so many we admire, but a few stand out.

The Lostwithiel Giant Parade, founded by our family in 1990, has to be our top pick. Not only is it our reason for being, but it is also a brilliant example of how a town can take ownership of a tradition and let it grow into something truly joyful and shared.

The Salisbury Giant, Christopher, needs a mention. As the oldest surviving processional giant in Britain, he is a powerful example of how giants can adapt over the centuries when they are cared for by generations.

I have huge admiration for Giant Master Dave (Dave Roberts), who pretty much single handedly revived the Chester Midsummer Watch after a 300-year gap in history. His commitment to re-building the original giants and beasts using 16th century techniques and materials is inspiring to say the least.

Outside of the UK, Bread and Puppet Theatre in Vermont has been a big influence - their use of giants to carry political ideas with humour and mischief really resonates with our own playful, slightly rebellious spirit. Similarly, Theatre of the Ancients in Ibiza are doing inspiring work reconnecting procession and performance with landscape, myth, and story.

Interview by Daniel Farnham. Images courtesy of The Lost Giants.